In technology-centric product development organizations, promoting and retaining talent while fostering a culture of technical excellence is essential. An established role of Subject Metter Experts, or SMEs, has proven to be an effective way to facilitate knowledge excellence, particularly in multi-project organizations.

Steve Jobs once noted, “It doesn’t make sense to hire smart people and then tell them what to do. We hire smart people so they can tell us what to do.” However, hiring costly experts and hoping for the best is usually not enough. A certain level of organization and hierarchy, stemming from knowledge and experience rather than from formal authority, is crucial if your organization is to outperform the competition in fast-paced technology environments. Expertise and diversity are both required as this could result in a risk of communication failure. If two “stars” are hired to lead similar tasks, they will likely have different approaches on several levels. The resulting friction may have severe consequences for the team or even the entire organization. For example, if an expert is convinced that using the concept of use cases for requirements engineering is the best approach, while the other expert prefers using agile user stories without clear leadership, such discussions may result in endless disputes. Thus, technical leadership should not be left to chance. In his well-known book Knowledge Management Systems, Ronald Maier emphasizes the importance of “process owners.” However, since the term process owner may sound suspicious, especially in the context of an agile environment, I prefer the term “Subject Matter Expert”, also mentioned by Ronald Maier. Subject Matter Expert, or SME, promises meaningfulness and conceptual elegance. In technology-driven organizations, key concepts such as “project management”, “configuration management” or “test management” are already well established across many industries. In such organizations, for instance, “software requirements engineering” can be performed various numerous approaches, methods, and tools. To ensure consistent methodology and to implement an effective quality assurance policy, a “Requirements SME” may be established to align all those aspects for the current project as well as across projects and departments. Further examples of an SME may include:- Configuration Management SME

- Project Management SME

- Software Engineering SME

- System Architecture SME

- System Test and Validation SME

- Software Test and Validation SME

- Quality Assurance SME

SME responsibilities

The responsibilities of an SME include:- Defining process concepts and definitions (this correlates with Ronald Maier’s “process owner”) roles, including process descriptions, work instructions, templates, checklists, and other process assets

- Defining appropriate methodologies, such as tools, notations, modeling practices, etc.

- Participation in technical and management reviews

- Peer-reviewing the work products in the scope of the SME’s competency

- Providing training, training materials, and hands-on support in the respective subject matter

- Reviewing and approving new hires in his or her scope

- Peer-reviewing other SMEs’ process documents.

SME skills

An effective SME exhibits specific skills and qualities, such as:- An extensive experience in the corresponding technical role

- Extensive experience in the related industry

- Appropriate educational background (typically of an academic kind)

- Strong preference for structured and systematic approaches

- Acceptance and authority among the peers

- Deep awareness of process quality aspects — particularly in your specific industry — which includes good knowledge of the respective standards (such as Automotive SPICE, ISO 26262, etc.)

- Good command of standard management techniques and methods

- Passion for your subject matter and willingness to help your peers in the same subject matter area

- High emotional intelligence

- Novice (only follows context-free rules)

- Advanced Beginner (uses new situational elements. Decisions are still solely based on rules)

- Competent (the number of rules has grown large, available information is prioritized, self-organizing)

- Proficient (first intuitive decisions, holistic thinking begins, verifies own intuitive decisions using rational patterns)

- Expert (holistic thinking, including decision-making and planning)

An effective SME

The combination of technical and personal skills is as uncommon as it is essential. Even the best technical skills and knowledge may prevent an SME from being effective if the SME cannot demonstrate a high level of emotional intelligence. Such a delicate balance of skill and emotional intelligence is fragile. The risk of alienating the peers that the SME is supposed to lead should be taken very seriously. I firmly believe that for an SME, a high amount of humbleness is often beneficial. Other experts will not follow the SME if they feel oppressed or manipulated. An SME leadership is best demonstrated by knowledge, experience, and willingness to listen. It is also important to emphasize that, to be effective in the SME role, an SME must have the authority to make substantial decisions in the scope of the subject matter in agreement with other SMEs. That includes tools, methods, development approaches, and methodologies. At the same time, an SME must never appear dangerous to senior management. Otherwise, an SME may become ineffective and even redundant. Consequently, an SME must be directly explicitly empowered by the top management and become a respectable role, forming a strong connection between their project team(s) and the rest of the organization. Furthermore, the SME must not be excluded from first-hand, continuous project experience to stay in touch with the subject matter reality. It is recommended for an SME to continue work that corresponds with the SME role. An average of 20% of the SME’s working time on project assignments is recommended.An SME organization

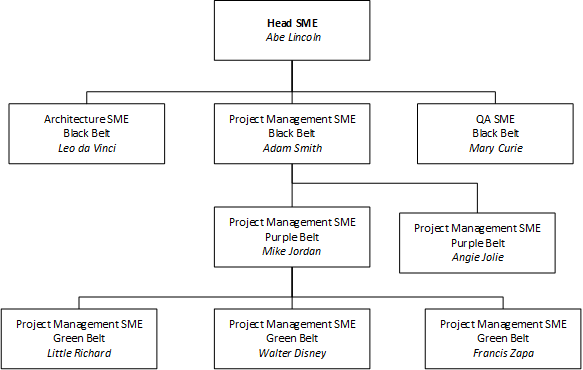

As previously mentioned, an SME should not share the subject matter responsibility equally with another SME in the same field to ensure effective decision making. This raises the question of the availability of an SME. As the organization grows, at some point it becomes impossible for a single person to provide advice, training, coaching, and other services to multiple teams. Thus, defining the role of a lead SME becomes unavoidable: one person is chosen to be the “super SME”, while other SMEs in the same subject matter area follow the lead SME. Furthermore, in large organizations, there may be several levels on an SME expertise, organized hierarchically similar to the martial art of Judo, such as “Green Belt” (competent), “Blue Belt” (proficient), and “Black Belt” (top expert, for the lead SME), in analogy to Dreyfus’ expert levels 3 to 5. The following (incomplete and hypothetical) example illustrates a hierarchical SME organization:

Difference between “process expert” and “subject matter expert”

There is a common misconception that every process needs a dedicated owner. In standards such as CMMI or Automotive SPICE, the concept of a “process” has been misused by assuming that a “process” is an independent, self-contained task. Unfortunately, the transition from CMMI to Automotive SPICE amplified the problem with a “process” as a separate entity. In CMMI, the process disciplines were called “process areas” while in Automotive SPICE, those areas are now called simply “processes,” which suggests that development processes are part of the sequential series of concluded activities. While this is true in some instances, such as a kicking-off, the delivery of a system follows a project, it is not helpful to have a cascading chain of events in all cases. Instead, certain activities, such as “software requirements development” or “software integration testing”, naturally concentrate on experts who rarely are identical with the Automotive SPICE processes or process areas in CMMI. For example, in CMMI, having a “process owner” for the risk management process area “RSKM” is rarely useful as a separate “process.” Similar applies to the Automotive SPICE “MAN.5” (“Risk Management”). Having separate “process owners” for each process or process area typically results in redundant project organizations that frequently argue over the responsibilities. The following example demonstrates a possible SME and Automotive SPICE coherence (mostly limited to the VDE scope):| SME | Automotive SPICE process |

| Requirements SME | SYS.1 “Requirements Elicitation SYS.2 “System Requirements Analysis” SWE.1 “Software Requirements Analysis” |

| Architect SME | SYS.3 “System Architectural Design”SWE.2 “Software Architectural Design” |

| Software Development SME | SWE.3 “Software Detailed Design and Unit Construction” |

| System Validation SME | SYS.5 “System Qualification Test”SYS.4 “System Integration and Integration Test” |

| Software Validation SME | SWE.6 “Software Qualification Test”SWE.5 “Software Integration and Integration Test” SWE.4 “Software Unit Verification” |

| Project Management SME | MAN.3 “Project Management”MAN.5 “Risk Management” ACQ.4 “Supplier Monitoring” SPL.2 “Product Release” |

| Quality Assurance SME | SUP.1 “Quality Assurance” |

| Configuration Management SME | SUP.8 “Configuration Management” |

| Issue Management SME | SUP.9 “Problem Resolution Management”SUP.10 “Change Request Management” |

Advantages of an SME organization

An SME-driven organization has many advantages:- Technical experts do not have to be forced to become traditional managers. Instead, SMEs can remain in their favorite expertise areas.

- Consequently, an SME career helps retain talent, reducing churn and retaining expert knowledge within a technical organization.

- Since SMEs tend to be more experienced and dedicated, they are more likely to be immune to technical and management hypes.

- Fostering the project-oriented culture instead of exposing project teams to strong matrix organizations which is, by its very nature, averse to change, helps achieving tangible project goals.

Let’s start a conversation on LinkedIn or X.com (formerly Twitter).

I am a project manager (Project Manager Professional, PMP), a Project Coach, a management consultant, and a book author. I have worked in the software industry since 1992 and as a manager consultant since 1998. Please visit my United Mentors home page for more details. Contact me on LinkedIn for direct feedback on my articles.

Be the first to comment