Asking the right questions is the way to unlock the true power of AI. That gives experienced professionals an unexpected edge; everyone can profit from that.

The recent wave of AI (and ML–machine learning) is a technological advancement and a paradigm shift that redefines how we perceive and interact with technology. However, it can also be frustrating if not handled properly.

In the popular book “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” a computer has spent millions of years calculating the answer to the “life, universe, and everything.” The final result was disappointing:

“Forty-two!” yelled Loonquawl. “Is that all you’ve got to show for seven and a half million years’ work?”

“I checked it very thoroughly,” said the computer, “and that quite definitely is the answer. I think the problem, to be quite honest with you, is that you’ve never actually known what the question is.”

Is AI the answer to everything? At any rate, AI is all over the media landscape. It has captivated the fantasy of people from all walks of life: developers, tech entrepreneurs, managers, stock analysts, and the media. AI seems to be becoming the ultimate “silver bullet.” I lived through the tech bubble that burst in 2000, and it begins to feel a bit like what happened 23 years ago. During the dot-com frenzy, thousands of startups failed without producing anything but empty cubicles and disappointed investors. However, the cards have been recently thoroughly shuffled with the dawn of generative AI. ChatGPT, for instance, can produce surprisingly helpful results. Despite having tested it extensively for many months and experiencing a subtle disillusionment creeping into my subconscious, one fact remains undeniable: ChatGPT does a decent job at many things, such as coding, problem-solving, and summarizing large text passages. Despite occasional “AI hallucinations,” ChatGPT is not a fantasy or the next boo.com; it’s real – as real as an “artificial” thing can be. Consequently, billions are invested in its further development. Thus, concerns about eliminating certain professions and replacing them through AI seem justified.

AI won’t replace humans. The humans skilled at using AI will.

However, if you fear that the next Skynet is about to eliminate the entire humanity, then I have some good news. Just like with other software solutions, such AI-based tools still suffer from the “garbage in, garbage out” principle: the output depends on the quality of the prompt. The more complex the expected result, the more critical it is to ask the right question. Even seasoned professionals often need many attempts to achieve useful results using ChatGPT. The success rate is lower if the questionnaire lacks genuine expertise.

The recently advertised “GPT Prompt Engineer” profession demonstrates this dilemma. It is just another re-incarnation of the “Internet Researcher” that became popular in the years of the dot-com boom back in the 1990s. It eventually became obsolete with the increased internet literacy and the invention of the Google search engine.

That said, another “Google” may or may not be invented anytime soon. An AI prompter–an AI manager of an AI manager, if you will–would have to be able to interact with humans in real time to understand all tasks on all levels fully and swiftly. It may be possible to develop such a “real-time manager” for relatively simple jobs, such as managing a call center or organizing certain logistical tasks, like running a warehouse. However, significantly more complex tasks that require technological creativity, such as new systems development, pose an entirely different challenge. For example, not only must a developer of a safety-relevant car system be carefully designed, but ensuring the safety of such systems implies making highly complex decisions on every development level, from requirements, architecture, and code to testing such systems. In addition, the decision on the overall functional safety of a new car (safety case) must be evaluated and proven viable based on the personal experience of a team of highly qualified human experts. It is a legal challenge that cannot be delegated to an AI system in the foreseeable future. In other words, the safety of a system, such as a passenger car, for instance, is a highly personal task.

The perils of “delegate to innovate.”

The advent of AI technologies such as ChatGPT, Bard, & Co. has shifted the focus from the actual work that needs to be done to what can be done and how it can be done. Genuine insight is the key, comprising two parts: a good question and the right answer. Just like in the novel “Hichhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” where asking the right question was the key to an answer that no one could understand, in the real world, the questioner’s skill must be excellent if the right answer is what we expect.

In other words, not working hard on a task but cleverly delegating tasks to an AI system is the future of work. There is, however, a subtle problem with that idea: for that approach to succeed, the tasks must be very well-defined and based on a deep understanding of the context and technical knowledge. Using facts instead of assumptions is at the core of successful systems development, but going for a “quick win” (or using AI to harvest “low-hanging fruits”) can backfire. That’s because natural academic and technological curiosity may become inconvenient in a world where nobody really has to do any research because AI systems do it.

And therein lies the risk: we might become a society where professional and technological excellence is no longer expected. “Satisficing,” a term created by Nobel laureate Herbert Simon, may be the new zeitgeist. According to that idea, humans often cannot find the best solution, so maybe we shouldn’t try. Let’s take what appears good enough.

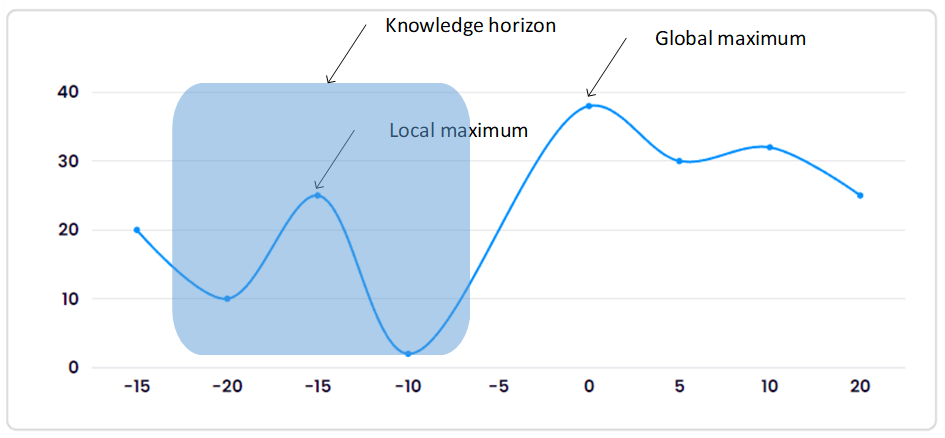

However, as renowned inventor Charles Franklin Kettering, who filed some 300 patents, said a century ago: “High achievement always takes place in the framework of high expectations.” If that simple wisdom becomes degraded to “fake news,” we can become a society where mediocrity becomes a cultural norm. Using calculus as an analogy, we may be tempted to choose “local maximum” results instead of relentlessly searching for the “global maximum.”

Humanity, however, has become successful precisely because we refused to succumb to our circumstances. We don’t settle for “good enough.” Despite frequent setbacks, we have continuously extended our options by understanding more of our world and using it to our advantage. In that spirit, to achieve the best possible result, as opposed to a “good-enough” one, the “broader picture” is required. By that, I mean using a larger body of knowledge instead of just a fragment of it–a knowledge “horizon,” if you will. Extending our intellectual horizon has produced incredible results in the past by discovering what we haven’t even been looking for. But how to resolve the conundrum of not knowing what we don’t know? Waiting for random enlightenment is no longer viable; we need to move faster.

Enter Yodas

Herein lies a remarkable opportunity for seasoned professionals. Over the years, as specialists in our respective fields, we have accumulated invaluable knowledge, expertise, and intuition. We know the industry landscape, understand the subtleties, and see the bigger picture. In the emerging age of AI, it may not be the cheapest workforce that adds value, but it is the most experienced one who instantly knows what to look for without just hoping to guess a working prompt.

What is that mythical “experience?” In the tech world, experience is not just the time spent in your company in a particular position. Instead, it is the time spent on solving complex problems. That’s the learning process that results in the accumulation of expert knowledge. Over time, the knowledge becomes condensed into wisdom, of which the vital portions can be reused and integrated into the decision-making process, resulting in technical, interpersonal, leadership, and managerial expertise that can be shared with others around you. That kind of wisdom is what I occasionally call “Yoda wisdom”–loosely referring to Yoda from the iconic saga “Star Wars.”

Like the Star War Yodas, “our” Yodas are sought-after in times of need. A Yoda is a business mentor, project coach, project coordinator, or career coach. Yodas are the right persons to ask the right questions. The right answer often automatically follows. It is not just expertise but practical wisdom that adds decisive added value to each organization or project.

The right question can be half the answer.

Some industries, such as my favorite vehicle development industry, need a Yoda more frequently than others. In particular, when another complex auto part development gets in trouble, help is desperately needed. It’s not surprising since such projects consist of many moving parts: customer requirements, industry standards, various contradictory agendas (such as “agile” vs. “V-model”), technological challenges (e.g., novel technologies required for AI-based autonomous driving parts), challenging profitability expectations, tight time constraints, numerous safety and security requirements, and many more. Efforts and risks in such projects are notoriously underestimated. Thus, even a well-trained chief engineer often doesn’t realize that the project is already in serious trouble until the first crisis meeting with the customer is summoned. The result is often a seemingly endless stream of “task forces,” on-site colocations in customer offices, and a combination of fear, threats, and borderline burnouts. Had a Yoda been involved in such a project from the beginning, all those unpleasant circumstances would most likely not have occurred.

Consequently, a Yoda should be hired early in a project to ask the right and critical questions. Once on board, after a short time, a Yoda already knows the project’s key risks and the team’s strengths and weaknesses. The situational analysis is complete when the Yoda has discussed the project with key stakeholders, such as the customer and the critical suppliers. There is no need to perform a formal “gap analysis” or “process assessment” (such as Automotive SPICE assessments). A Yoda knows from year-long experience what is “going on” and can immediately begin “saving the project.”

A Yoda, however, cannot win a stellar war alone, and a similar insight applies to our Yoda model.

The other half of the equation

At this point, the Yoda focuses on the team’s performance and the future role of AI in modern projects.

But what is “team performance?”

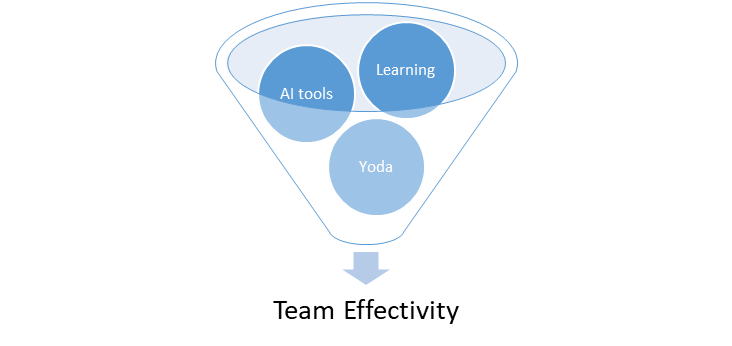

The team performance is increasingly all about the ability to use the new AI tools in the best possible way to achieve faster, safer, more secure, and more customer-oriented results. Finding a smart combination of the right AI tools and the right skills to utilize them efficiently and effectively will prove mission-critical. For that reason, in this new AI universe, “team performance” is becoming more mission-critical because fewer experts can (and must) achieve more than it has ever been possible with conventional methods and tools. Consequently, while increasing the headcount by hiring cost-efficiently (read: cheaper) has long been the conventional strategy, it is quickly becoming obsolete. In other words, you want to keep your team as small as possible while using AI to leverage the team’s performance. At the same time, those expensive experts and high-potentials need the right advice to prevent making avoidable mistakes. Therefore, the team’s performance is a function of “Yoda + Team + AI.” That is the success formula of the AI future.

Crucial success factors

The following factors are decisive in the age of AI:

Continuous Learning: the first success factor in implementing this strategy is establishing an agile learning culture in your project organization. Such culture is critical in this industry and must be adapted willingly and without hesitation. Asking questions and finding answers is a crucial learning process for the entire team. Questioning the status quo must not be shone but actively encouraged. The learning curve must be steep. A Yoda facilitates the necessary sense of urgency and training a higher learning pace. The teams are then expected to pounce at the task and fiercely attack the problem. In the meantime, actively training your team is absolutely crucial. In my opinion, however, the traditional external form of on-site frontal training has become hard to implement as the teams don’t have the time to spend several weeks attending various workshops and on-site training sessions. That brings me to the next point: learning and AI are a wonderful combination.

Using the right AI and ML tools is becoming mission-critical. That corresponds well with the continuous learning paradigm. Using a generative AI tool like ChatGPT, for instance, while currently not perfect because of the notorious problems with the reliability of its results, is becoming a serious competitor to conventional training methods. For instance, ChatGPT (or Bard, for that matter) can significantly help you learn new programming languages. With a simple prompt, such as “I am a computer scientist with good knowledge of ANSI C and C++, and I want to learn Python,” ChatGPT immediately produces tips and tricks on how to start learning. Just ask to create a “hello world” app, ask how to install Python and what IDE to use, and you can learn away. You can also ask for more complex examples, such as code for specific ECUs, and you might be surprised how much ChatGPT knows about that. It is also a fantastic assistant for debugging your code. Of course, ChatGPT does not always give the correct examples; they sometimes produce compiler errors, and occasionally, the results are completely useless. And yet, it is a great start and worth the effort to explore more possibilities. And it can only get better in the future.

ChatGPT can also be used for more challenging learning tasks. For instance, with a well-designed ChatGPT prompt, it is easy for a skilled developer to learn more about the functional safety standard ISO 26262. It can generate a complete training outline. Then, the developer can drill down into each chapter and explore the standard in detail. That boosts morale and learning speed because the developer does not have to wait for the availability of a trainer, and the barrier created by the fear of “asking stupid questions” does not exist with an AI learning approach. Also, the developers do not have to waste their time on things they already know. They can directly skip to the next chapter. Again, while the quality of such automatically generated training material is still too low to replace a professional trainer, the gap between the two is rapidly narrowing. Also, a Yoda offers great help in this regard because a Yoda can help design the right query, verify the correctness of the AI-generated results, and point the team to the most promising way of using ChatGPT or Bard.

Learning with ChatGPT is just one of many ways to use AI in a project. AI has become so ubiquitous that it is nearly impossible not to encounter it in virtually every automotive discipline: supply chain management, hardware development, software development, testing and validation, project management (on all thinkable levels), manufacturing, supplier management, car sales, end-user support, etc. Specific vehicle solutions are also rich in AI: vision systems, ADAS software, in-car software (e.g., when the driver is not alert or even about to fall asleep), and many more. Seemingly, everything has become “powered by AI” now.

In systems development, some such tools are already well-known in the automotive development community and are being actively embraced. Here are a few examples:

- GitHub Copilot – AI-driven predictive coding assistant

- Parasoft C/C++ ML-based automation of the creation of test specification

- Tabnine:Predictive code editor, analog to Github, mainly for non-embedded purposes, as it does not offer C/C++

- Snyk (previously DeepCode)

Further use cases for AI-embedded development include bug detection, code refactoring, requirements quality assurance, and debugging capabilities, all based on AI solutions. Also, systems like ChatGPT and Bard can significantly accelerate learning new libraries and tools.

As a side note, AI tools must be thoroughly scrutinized regarding privacy and security, especially if they are “cloud tools” (read: someone else’s database).

The broader picture: the future of learning is… learning

The risk of the entire generation losing their intellectual edge is real. Not only the convenience of using AI and “getting over with quickly” poses a danger of losing the engineering prowess. We need a fundamental shift in how we approach education. It’s disturbing that our current system often stifles curiosity, creating more followers than leaders and more conformers than questioners. This must change. We must revive the traditional, scientific, and technology-oriented curiosity rooted in critical thinking, problem-solving, and the spirit of innovation. The rampant political correctness must not snuff out the spark of intellectual curiosity. We must encourage young professionals of late to question, explore, and push boundaries. Combining human ingenuity and AI capability can yield unprecedented outcomes if we can create an environment where curiosity thrives.

The future of work is learning. Maybe learning to learn again as well. A lack of critical thinking produces followers, and we need them, too, but we also need leaders. To be a leader, you must be curious, but curiosity, so it feels, is not encouraged. Political correctness is “killing us” and must be immediately replaced by traditional, scientific, and technology-oriented curiosity so that tech professionals’ current and future generations can grow and produce much more output than input. In that sense, the rise of AI in the form of generative AI and others can be the best thing ever for the global economy.

The age of Yodas is here.

AI doesn’t render us obsolete; it only redefines new or different skills. This potential employment crisis presents a great opportunity, especially for seasoned professionals who have spent years in the trenches of software development, project management, and quality assurance.

As tech industry veterans, we’re well-equipped to navigate these changes and to guide the next generation through them. Let’s embrace this opportunity and show the world what we can do when humans and AI work together. Let’s ensure that our questions, not just our answers, drive the future. The game is changing, but it’s just beginning in many ways. And we have the privilege of playing a vital role in this game.

The rise of AI is not a threat but an opportunity for seasoned professionals and curious, young experts. It is a chance for us to leverage our knowledge and experience to guide the next generation of tech professionals. It is a chance for us to redefine our roles and significantly contribute to the global economy. Let’s embrace this opportunity and make the most of it.

Let’s start a conversation on LinkedIn or X.com (formerly Twitter).

I am a project manager (Project Manager Professional, PMP), a Project Coach, a management consultant, and a book author. I have worked in the software industry since 1992 and as a manager consultant since 1998. Please visit my United Mentors home page for more details. Contact me on LinkedIn for direct feedback on my articles.