After “Management-by-Objectives” (MBO) didn’t live up to its expectations of both employees and managers, its successor, “Objectives and Key Results” (OKRs), came to the rescue. While the OKRs approach is currently being held in high regard on the organizational C-levels, the link between strategic goals and execution of those goals remains an open challenge. The good news is that this gap can be easily addressed and fixed.

Intentions, goals, strategies, and agendas are not automatically on the proverbial “same page.” Complex organizations have countless moving parts. It takes a lot of hard work and organizational talent to build a great team. Defining expected results that are realistic, objective, measurable, fair, politically correct, and corporate policy-compliant can be a daunting task. However, reviewing and verifying the related results is often even more difficult and a truly terrifying minefield for a manager.

In this article, I am looking into the most widespread goal-setting strategies and focus on specific types of objectives that are crucial to customer-related deliverables.

A Brief History of Managing Objectives

A long time ago, during the first industrial revolution, micromanagement was the way to manage both commercial and government organizations. It was probably the only way to make sure work was done as intended. It was a rational idea 100 years ago, but with the progress of more complex machines and methods, micromanagement has become unsustainable.

“Scientific Management,” invented by Frederic Taylor, was meant to be a remedy to that micromanagement challenge. Frederic Taylor and Henry Ford were successful with this method. From our contemporary perspective, such a system was an inhuman “command-and-control, authoritarian” management style, in which the factory production numbers were all that counted. Nevertheless, even though some don’t want to admit it, the Scientific Management approach was hugely successful. It resulted in lower prices and enabled car ownership for the masses. But not only Ford management but also Ford’s workers were quite happy with the new approach: the compensation was automatically better when the production increased. It was a win-win breakthrough for the entire company. Compared to the micromanagement approach, Scientific Management was more objective and less prone to bias and compensation randomness.

Over the years, the nature of work was changing again as the traditional workers were becoming “knowledge workers.” The Scientific Management was replaced by “Management By Objectives” (MBO). MBO seemed like a logical fix to the problem of the increasing complexity in the human field of resource management. MBO was developed by the famous management consultant Peter Drucker and described in his 1954 book “The Practice of Management.” On its surface, the implementation of the MBO concept appears straightforward:

- Review organizational goal(s)

- Set worker objective(s)

- Monitor progress

- Evaluate

- Give reward(s)

If MBO sounds like it was too good to be true, it’s because it was. Simply agree on the goals and wait until the goals bear the expected juicy fruits – that was the management’s hope. MBO was supposed to be the holy grail of a hands-off, efficient, and generally better leadership strategy. It is hard to argue that, at least in theory, it was a rational and promising strategy. And yet, MBO was intrinsically flawed, as it was tied to financial results. In other words, an employee who missed an MBO target suffered a financial loss; The bonus was axed. It is easy to see how MBO tends to destroy trust and leads to “dog-eat-dog” competition within teams. In hindsight, the MBO was obviously deeply flawed and couldn’t possibly work. But it was certainly well-meant.

MBO’s successor, Objectives and Key Results (OKRs), was the next improvement iteration. The OKRs are fortunately not tied to financial results. In addition to measurable goals, the plan “how to get there” is required. The results are measured quarterly or monthly, not yearly, as with the MBO approach. The OKRs idea revolves around the so-called “superpowers,” namely:

- focus and commitment to priorities,

- alignment and teamwork,

- tracking and accountability, and

- setting ambitious goals.

OKRs was an idea by no other than Intel’s co-founder Andy Grove (see Grooves the 1983 book High Output Management), and further elaborated by John Doerr, who was also an Intel employee. In his book “Measure What Matters,” he was especially inspired by the energetic young Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, which explains why Google is the parade advocator of the OKRs approach. Other companies followed that trail: Amazon, Twitter, Microsoft, Samsung, and many more (see a sample list here).

Here is an example of a quarterly OKRs by Intel, dating back to the year 1980:

Deliver 500 8MHz 8086 parts to CGW by May 30

KEY RESULTS

Develop final art to photo plot by April 5 Deliver Rev 2.3 masks to fab on April 9 Test tapes completed by May 15. 4. Fab red tag starts no later than May 1.

These are obviously “executive-level” goals that reveal the apparent weakness of the OKRs: they are “high-level” and not immediately actionable. They are, at best, what a professional project manager would call “key milestones.” The way to achieve the results on the organizational level remains unspecified. In principle, OKRs appear self-explanatory, but the devil is in the detail. Therein lays a weakness of the OKRs that should be addressed: how to define a good strategy of implementing key results?

The Missing Link in the OKRs Approach

OKRs authors mentioned that their approach, as opposed to MBOs, is “nimble” and “agile” because of faster result reviews, namely on a quarterly basis. In my opinion, quarterly results reviews do not sound particularly “agile” nor “nimble.” What’s even more surprising is that Doerr’s book on OKRs is pretty recent, namely published in 2017, and a quarterly OKRs tracking may appear already relatively slow and not what we expect in the hectic new age of the ever-accelerating corporate world. In the Scrum methodology, for instance, established some 20 years ago, a retrospective of just two weeks was recommended. Shouldn’t the OKRs be reviewed more frequently, possibly monthly or even be-weekly? And if so, how exactly should we go about the results planning and their reviews?

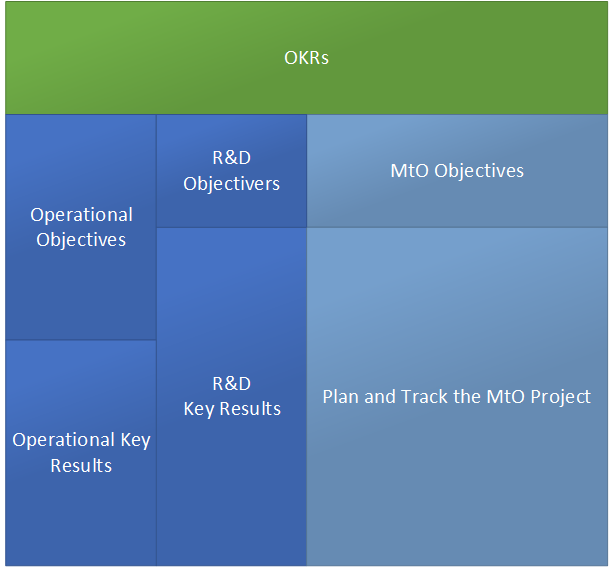

A more analytical approach can further help resolve this riddle. The following picture illustrates a principle structured goals and results:

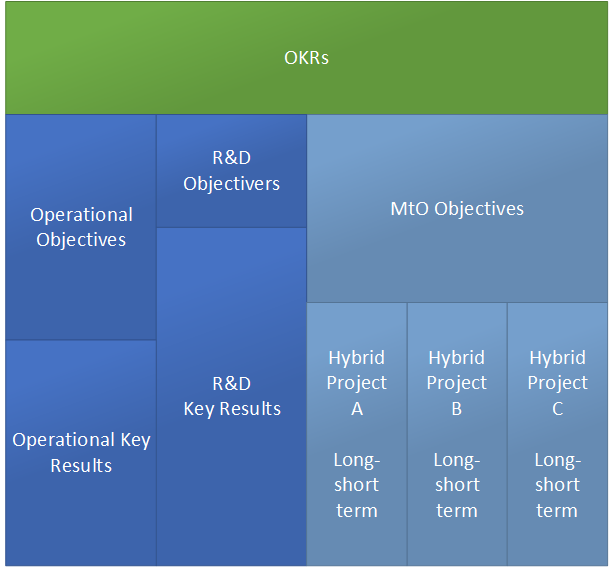

In the above chart, I have proposed to break the OKRs down into two blocks: operational objectives and product development objectives. Since the complexity of product development is usually higher than the operational objectives, it appears reasonable to focus on the prior to identifying bottlenecks in the flow of objectives and results.

Development objectives will frequently result in projects. For lower-paced environments, such as R&D (Research and Development), in which the product development takes more time to consider various design alternatives and incremental design maturity. Results will often be reviewed weekly or even monthly. In the case of MtO projects (see the article The Right Genes for Your Project for more background on the MtO project type), the results must be planned, estimated, reviewed, verified, and reported considerably more frequently to quickly identify quality and project timing bottlenecks and risks. An MtO project progress, therefore, is often reviewed weekly or even daily and should be treated differently from R&D projects.

Focusing on MtO projects already helps to focus on specific goals, but the above OKRs decomposition still does not bring clarity regarding the specific planning steps. The SCRUM approach is expected to be a “one-fits-all” solution to that challenge. The project backlog is simply iteratively and incrementally implemented and outcomes the desired product. The practical experience teaches us that, however, particularly in MtO projects, a backlog must not only be prioritized but also thoroughly structured and “end-to-end” planned to allow for effective risk management. On a very rough level, project planning is a process that typically takes longer than one or even several fortnight sprints. Thus, at least two levels of the project plan should be considered:

- Short-term planning and results tracking (Epics and Sprints, typically weeks)

- Long-term planning and results tracking (spanning months or even years)

The “big room planning” is supposed to resolve the long-term planning problem. According to that idea, an “all-hands” session (or several sessions) takes place frequently, and the team resolves the planning problem organically. This strategy often fails for a variety of reasons, including the following:

- It is frequently impossible to collocate the entire team for several days. That becomes more problematic if the big-room planning should happen more frequently, which is intended by the Scrum methodology. It is even more challenging in unusual situations such as global pandemics.

- Complex architecture decisions are rarely possible in a large group.

- In larger teams (more than around 15 persons), it is almost impossible to keep the entire team focused on a specific problem during the planning session that can sometimes take several days. The rest of the team is often neither qualified nor interested in the in-depth discussion.

- Off-site big-room planning is often expensive. Frequently, neither the management nor the customer accounts for such costs.

- The moderation of the big-room planning may fail due to a lack of professional moderator’s training and/or internal, political conflicts within the team.

Therefore, the connection between the key results (key milestones) and objectives (strategic expectations) is often hard to establish. The Scrum methodology fails to take the long-time planning into account. For MtO projects, on the other hand, the customer typically insists on a complete schedule from day one to the final release. The lack of such planning—the “red box” in the above chart—poses a critical gap between the high-level nature of OKRs and the implementation of short-term results.

OKRs by Projects

The implementation strategy of key results in an MtO project requires systematic short- and long-term planning integration. Unstructured planning is naturally nearly impossible; imagining a “backlog” as a loose list of ideas is not perceived as “professional” by strategic stakeholders. Therefore, a structured planning approach, typically based on the system architecture, created individually or in a small expert team of system architects is needed. However, assigning dedicated roles like an “architect” contradict the SCRUM methodology, in which no roles except the product owner and the scrum master are allowed. In larger teams, however, roles are crucial to ensure that certain tasks are performed by uniquely and consistently qualified experts. Therefore, the planning must be structured according to specific project roles, such as system architects and dedicated test leads.

At this point, it should be strongly emphasized that there is no contradiction in terms between agility and conventional project management. “Agility” is a fundamental mindset that is indispensable in today’s fast-paced product development. It is the limitation of the project structure to the inflexible Scrum methodology that poses an unnecessary organizational constraint. Especially in large projects, well-defined roles help to integrate multiple teams in a systematic manner.

A “hybrid” approach can solve this dilemma. Dedicated team roles can provide long-term planning, while short iteration cycles (e.g., based on 14-days-sprints) ensure that the team continuously produces visible results. In other words, a project needs both sprints and releases.

The “hybrid” project management is an excellent approach to implementing OKRs, in particular for MtO projects. The OKRs demand well-defined vital results, and the method of achieving them is automatically provided as part of the project management discipline. In other words, a well-defined hybrid project approach can be a natural implementation of OKRs; it is, if you will, “OKRs by Projects.”

In the above chart, projects A/B/C elegantly implement their key objectives. It is the very nature of project management to take the lead in delivering key results. The key results can take the shape of milestones, releases, or specific customer key deliverables in one or several OKRs objectives. Those partial results are defined in sprints.

The Bottom Line

There are many different leadership styles and recipes that it would be folly to assume that “OKRs by Projects” is the silver bullet of organizational leadership strategy. I have a whole pile of strategy books on my shelf; some are partially outdated, others still valid, some others have never been helpful in practice, and there are dozens of other sources I have not yet taken into account. However, an OKRs approach that integrates hybrid project management as part of the OKRs methodology is an elegant solution for customer-specific, customized products typically implemented as a MtO project in an agile organizational environment. As long as objectives and key results are defined in that way, no extensive customization of the OKRs is required. There is no need to develop any exotic means to determine, track, and verify the OKRs. The usual project management approach offers a number of standard metrics that can—and should—be used for that purpose. That eliminates the need to come up with new metrics.

A well-defined project management system is an ideal way to cultivate a leadership culture within the entire organization. Every project is a change, and managing change is at the core of the leadership mindset. The strategic advantage of a projectized approach also lies in reducing the amount of “corporate politics” within an organization.

It should also be noted that there are limitations to the “OKRs by Projects” approach. If running and delivering MtO projects are only a sporadic event, it would likely create an unnecessary overhead of developing a new, hybrid project management system. For example, an organization that focuses on continuous service delivery or rarely develops new products, the “OKRs by Projects” won’t be of great use. However, if an organization aims at becoming a “T-Rex Organization,” as described HERE, an “OKRs by Projects” approach can offer a significant competitive advantage.

Let’s start a conversation on LinkedIn or X.com (formerly Twitter).

I am a project manager (Project Manager Professional, PMP), a Project Coach, a management consultant, and a book author. I have worked in the software industry since 1992 and as a manager consultant since 1998. Please visit my United Mentors home page for more details. Contact me on LinkedIn for direct feedback on my articles.

Be the first to comment